As initially defined in our blog post *Top 5 Governance Considerations for Agentic AI[10]* and further expanded upon in our agent modeling series on the AI Fundamentalists podcast, this, as promised, is our “capstone”: The Agentic Travel Agent Mathematical Specification.

In this blog post, which is more technical than most, we will recap our Agentic AI Travel Agentic Series, briefly walking through the concepts of Mechanism Design, Utility Theory, and Optimizations, before arriving at the mathematical specification that brings the series together. To begin, we will review our agent’s description from our February blog post.

Let's consider a travel agent built using an AI agent. The guiding business need is for an agentic travel agent that doesn’t get tired and can be scaled infinitely to meet increasing customer demand.

Given the following LLM-based 4-step process:

Let's review the possible states of the system:

In each of these states, the goal is to ensure the accuracy of the city, times, budgetary constraints, and booking preferences. This can be solved using linear programming optimization techniques that are built for the optimization of constraints.

These components can be mathematically modeled and controlled with a ‘traditional’ programming user interface without requiring the high computational overhead of an LLM. When you introduce an LLM into the mix, the following ‘states’ need to be accurate, validated, and controlled to ensure the optimal customer experience:

If translation and state recognition are off in any section, there will be cascading error consequences of the action.”[10]

Alright, now that we’ve reminded ourselves what our use case is, let's provide a refresher for our intrepid, steadfast listeners. (i.e. a TL;DR of the key fields and methodologies covered in our series).

Mechanism Design is an interdisciplinary microeconomic theory focused on designing “the rules of the game” to achieve a desired outcome[4]. Essentially, it is reverse game theory, creating the rules of the game rather than analyzing the games.

The field draws heavily from microeconomics, optimization, and game theory. Initially introduced by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in their 1944 book, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior[3], it focuses on designing systems where the designer cannot know the agents’ preferences, and has asymmetric information[2].

Mechanism Design was constructed to:

Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanism

Vickrey–Clarke–Groves (VCG) mechanism [5,6,7] is a common Mechanism used to ensure that the dominant strategy for selfish agents is to always make a decision (choose a strategy) no matter what other agents may decide, rather than finding equilibrium through non-action.

Utility is a key concept within microeconomics and consumer choice theory, focusing on how individuals weigh choices[16]. Using utility, agents (in the economic sense of ‘rational actors’) make decisions that maximize their well-being, known as utility. Utility is often measured in ‘utils’, which are arbitrary, unlike money, such as the USD [15], that acts as a:

Utils are useful as theoretical units of measurement for determining how an individual makes a decision. In this case, the utils measure the value of each bundle of travel options. Utils can be either cardinal (categorical with an order, ex. ‘blue’ > ‘white’ > ‘red’) or ordinal (numerical, ex. 400 utils > 200 utils).

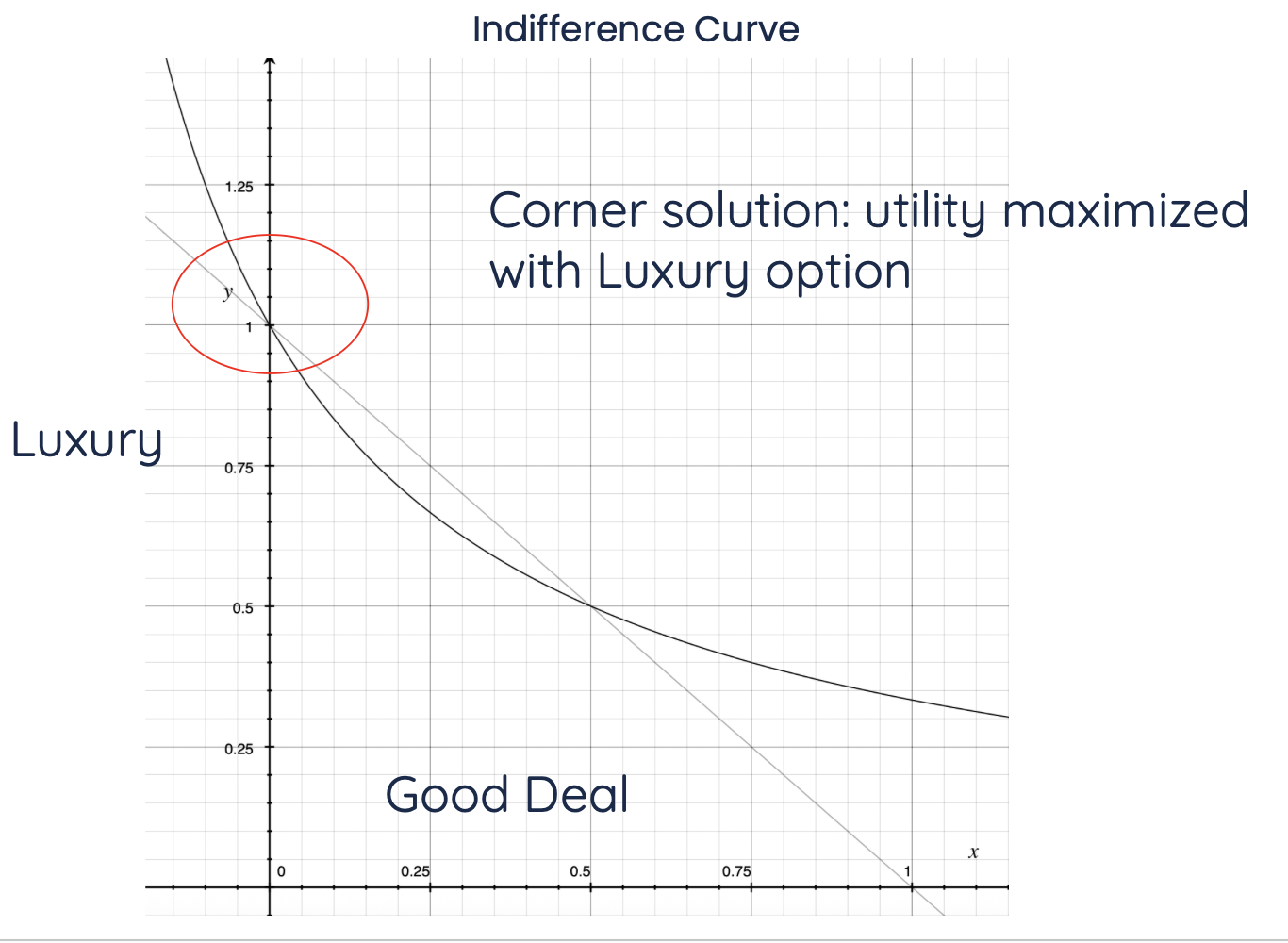

For an individual to determine their optimal ‘bundle’ of objects (i.e., a combination of flights, hotels, attractions, and restaurant combos), an indifference curve can be used to illustrate the set of “bundles” that the user would consider to be equivalent (Figure 1). All bundles along this curve return the same “utility” as derived from the agent’s utility function[16]. The slope of this indifference curve is the marginal rate of substitution: the rate at which someone is willing to substitute good ‘A’ for good ‘B’.

As we are operating within the discipline of Mechanism Design, the key takeaway is that different rational actors (agents) can have their utility functions, which could be learned from data or input programmatically. [***]

To solve our utility-driven problem, we will walk through several different types of solvers. Unlike the popular “give a prompt to an LLM and hope it has seen the problem during training” method, we want to optimize our given constraints to find the optimal solution.

For this section, we will do a whirlwind tour of several different optimization techniques, although this is a topic we’ve only begun to scratch the surface of within the Fundamentalists series. We strongly believe that the fields of operations research and optimization warrant a closer look in a quasi-Neuro Symbolic approach to AI[17].

Combinatorial optimization

Combinatorial optimization is a type of optimization that focuses on finding the optimal combination of objects. There are several classic problems with this space, such as the Knapsack problem[13]. In the Knapsack problem, you need to escape your home and you need to pick the most valuable items in your house to fit into a single knapsack (bag).

There are several ways to solve the knapsack problem, which is a classic computer science challenge, with our favorite being that of dynamic programming. Dynamic programming is a type of recursive programming paradigm where a complicated problem is simplified by breaking it down into simple sub-problems that are solved[13]

Branch and Bound: Breaking down the larger optimization into smaller sub-optimizations and using a bounding function to eliminate sub-solutions that cannot contain the optimal solution.

Another type of optimization is linear programming (and its extensions, integer programming and mixed integer programming).

Linear programming is the “simplest” variation of the three, where the variables can be any real number R in the form of[18]:

Linear programming problems are common; however, the assumptions of any real number (continuous) design variables are not practical for some use cases, including ours, where we need to only purchase 1 flight, not 1.555. In integer programming problems, the design variable (the variable that is being optimized for) needs to be discrete, ex. 1 or 2. And by extension, in mixed Integer optimization, both continuous and discrete design components can be utilized, e.g. our budget could be $550.50, but we can still only pick a single flight from a batch of possible flights.

Alright, now that we are all caught up on the underlying methodologies present, we will walk through the specific mathematical specification and how to solve our problem.

We will leverage Mechanism design - designing the rules of the game - for our formulation of the Agentic travel agent.

First, we will get some terminology/notation out of the way[4]:

We need to ensure that our agents are truthful about their reported type. To constrain the agents for truth-telling, we select the design $p_i$ to ensure that the optimum ‘equilibrium’ outcome. The mechanism itself is a tuple $\{f,p\}$, which is the social choice function $f: \theta\rightarrow O$ and a vector of payment functions $p=(p_i)_{i \in I}$ where $p_i:\theta \rightarrow R$.

In plain English, our mechanism defines the ‘rules of the game’ for the system objective of mapping agents’ types $\theta_{i \in I}$, to an outcome, constrained by optimal or efficient use of payments to satisfy an outcome[4]. The specific optimization problem is enumerated below:

More simply, we have adapted the constraints to our Agentic Travel Agent example, where we want to maximize the “social welfare” (SW) (equation 1) of our market mechanism. This allows us to optimize the consumer’s utility (maximize the allocation of resources, given each agent’s type, ex., budget traveler, budget airline, etc.) for the most tailored vacation that doesn’t exceed their budget. This is done while balancing the various producers’ utility by maximizing their respective revenues while minimizing cost[*].

Equation 2 states that the SW function is subject to every agent truthfully reporting their type and that we want to incentivize agent truthfulness (e.g. the push-pull of consumers wanting to low-ball their willingness to pay and producers wanting to squeeze out every last dollar of revenue). Rather, at any given time, we seek the optimal match to maximize everyone’s welfare by truthfully reporting their preferences and types (budget or luxury traveler, etc.).

Equation 3 is the efficiency condition for ensuring the efficient allocation of resources.

Equation 4 ensures that there are no external payments required (in this context, ‘bribes’ or collusion between agents outside of the mechanism - think ticket hawking or arbitrage).

Equation 5 states that all agents are voluntary participants in the mechanism.

Next, we will utilize the Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanism [5,6,7] to solve the optimization problem outlined above.

$f(\hat \Theta) = \arg \max_{o\in O, \hat \theta \in \Theta_i} SW(o,\hat \theta_i)$ (9)

To incentivize agents to report their private information, the VCG mechanism [4]:

$p_i(\hat \theta) = \sum_{j \ne i}v_j(f\hat \theta-i))-\sum_{j \ne i}(v_j(f(\hat \theta))$ (10) where $\hat \theta-i$ is the type profile of all agents but agent i. If all agents report truthfully, the first sum is the social welfare of all other agents without i, and the second sum is all agents, including agent i. This calculates the marginal effect (externality) of i on the total welfare of the system.

Given our system formulation, we will focus on the consumer type $\theta_c$, with airline agent type $\theta_a$ and hotel agent types $\theta_h$ are assumed to be reporting truthfully their utility maximization offers.

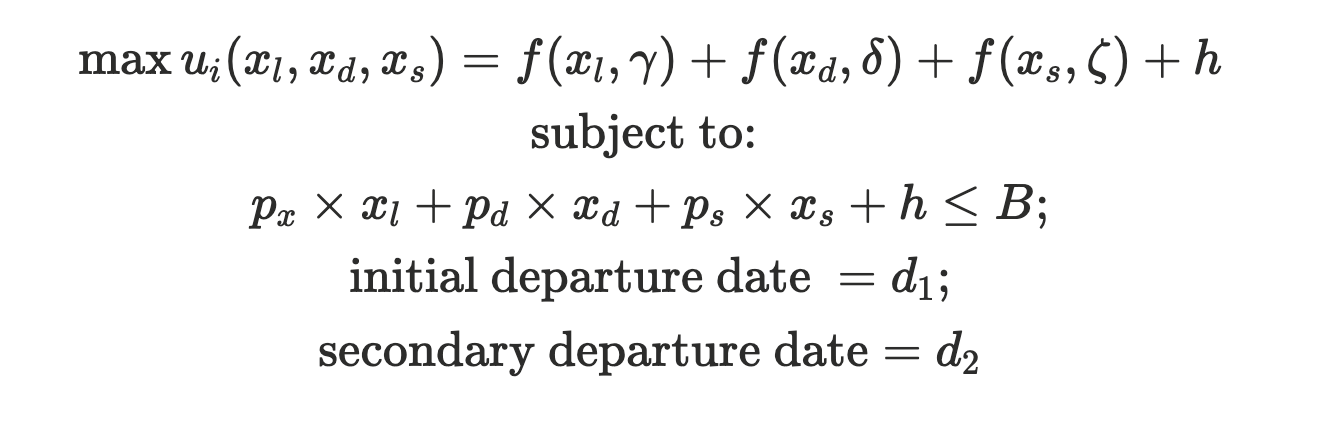

For agent type c, consumer, $\theta_c$, which is the only active type $\{\theta_c\} \in \Theta$ in our formulation, their utility function is:

Where:

$\gamma \in [1,10]:$ luxury preference

$\delta \in [1,10]:$ good deal preference

$\zeta \in [1,10]:$ shortest route preference

h: fixed at the median total cost of all hotels in the given destination city and dates

To solve efficiently, as defined above, we utilize a ‘combinatorial optimization’ Solver:

When we attempted to leverage a GPT-based system to create an additional end-to-end example based on the above, the logic and math were incorrectly handled by the model. The GPT system claimed that the optimal flight was under the budget, despite being over-budget (when there were flights, in its hypothetical example), that met the budget constraints.

In our 6-part series on Agentic AI, we have only begun to scratch the surface of this rapidly developing and exciting region of AI work. Hopefully, this series has been both as informative for the reader/listener as it has been for the authors. Our overarching goal has been, and will continue to be, presenting a sampling of the various solutions to AI problems. We stand that the most popular/common metaphorical hammer may not always be the best solution. In the case of a SaaS, or otherwise, based Agentic Travel Agent, there are more performant, secure, cost-effective, and governable solutions available to solve the problem.

Until next time,

The AI Fundamentalists

[*] ****An airline's optimal strategy may not always be the highest ticket price at the last minute but also predictability in revenue stream to enable optimization of fuel hedging, staff, and fixed cost (airplane) allocations. So an optimal “match” of a ticket between the consumer and airline may be a lower price level if booked earlier and/or on a less busy route that is not expected to fill in last minute with inelastic (meaning, not overly price sensitive) business travel (this is the topic of dynamic pricing, which is a fascinating topic for another day).

[**] ****Nash equilibrium is the state where agents make optimal moves while also considering the moves of the other players (an agent's optimal strategy considering other actions)[8]. The Nash and dominant strategies could be the same, but they are not always.

[]* This is out of scope for this article, but typically, an indifference curve is solved for its interior solution. In our example, given you can only purchase one travel bundle, e.g. “Luxury”, “Good-Deal”, or “Shortest-Route”, and not a combination.

[1] A. Mas-Colell, M.D. Whinston, and J.R. Green, Microeconomic Theory. New York, NY, USA: Oxford Univ. Press, 1995

[2] NobelPrize.org. “The Nobel Prize in Economics 2007 - Speed Read: Optimizing Social Institutions.” Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2007/speedread/.

[3] “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior | Princeton University Press,” April 8, 2007. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691130613/theory-of-games-and-economic-behavior.

[4] Chremos, Ioannis Vasileios, and Andreas A. Malikopoulos. “Mechanism Design Theory in Control Engineering: A Tutorial and Overview of Applications in Communication, Power Grid, Transportation, and Security Systems.” arXiv:2212.00756. Preprint, arXiv, December 1, 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.00756.

[5] Clarke, Edward H. “Multipart Pricing of Public Goods.” Public Choice 11, no. 1 (September 1, 1971): 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01726210.

[6] Groves, Theodore. “Incentives in Teams” Econometrica 41, no. 4 (1973): 617–31.

[7] Vickrey, William. “Counterspeculation, Auctions, and Competitive Sealed Tenders” The Journal of Finance 16, no. 1 (1961): 8–37.

[8] Investopedia. “Comparing Dominant Strategy Solution vs. Nash Equilibrium Solution” Accessed May 13, 2025.

[9] Harsanyi, John C. “Games with Incomplete Information Played by ‘Bayesian’ Players, I-III. Part I. The Basic Model” Management Science 14, no. 3 (1967): 159–82.

[10] “Top 5 Governance Considerations for Agentic AI” Accessed July 6, 2025.

[11] Apple Machine Learning Research. “The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity.” Accessed July 16, 2025.

[12] Huang, Kung-Hsiang, Akshara Prabhakar, Onkar Thorat, Divyansh Agarwal, Prafulla Kumar Choubey, Yixin Mao, Silvio Savarese, Caiming Xiong, and Chien-Sheng Wu. “CRMArena-Pro: Holistic Assessment of LLM Agents Across Diverse Business Scenarios and Interactions.” arXiv, May 24, 2025.

[13] Kochenderfer, Mykel J., and Tim A. Wheeler. Algorithms for Optimization. The MIT Press, 2019.

[14] Smith, Adam, and George J. Stigler. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Edited by Edwin Cannan. University of Chicago Press, 1976.

[15] Clark, A. and Mihailov, A., 'Why private cryptocurrencies cannot serve as international reserves but centralbank digital currencies can', University of Reading discussion papers, September 2019.

[16] “Utility Functions - EconGraphs.” Accessed August 4, 2025.

[17] Marcus, Gary. “The Next Decade in AI: Four Steps Towards Robust Artificial Intelligence.” arXiv:2002.06177. Preprint, arXiv, February 19, 2020.

[18] Boyd, Stephen P., and Lieven Vandenberghe. Convex Optimization. Cambridge University Press, 2004.